- Home

- Andrew Fukuda

This Light Between Us Page 24

This Light Between Us Read online

Page 24

“They’re up the hill!” Mutt shouts, pointing with his rifle. “Take cover!”

They scurry around the backside of trees, or lie squeezed up next to fallen trunks. What they should do: retreat slowly, from tree to tree, back down the hill to safety. Because fighting a well-fortified, well-armed enemy positioned on higher ground is a losing proposition. They must retreat.

But they don’t.

They hunker down. Then slowly, inch by inch, foot by foot, tree by tree, like men possessed, they press forward. Up the slippery slopes, cold mud sliding under their uniforms, sludging along their skin.

Until the Germans, even those on higher ground and better armed, find themselves staring at the wild, obsessed eyes of a mud-covered soldier throwing himself over the rim of their machine-gun nest and spraying bullets with a manic cry. Or watching a live grenade land into their artillery station, and rolling casually against one of their German boots. Or peering through the scope of the Walther G43 sniper rifle only to land on another sniper with his rifle pointed right back; a curious Kaugummifresser, this one, in an American uniform but why is there a Japanese face on—

Until the Germans find themselves overrun and overmatched.

By dusk, the 442nd has captured that hill.

But there are many more hills between them and the Lost Battalion. They covered only two miles today. Still three more to go. Three more miles into the heart of wet dark cold hell.

* * *

The next day, even worse. Hails of bullets gush down the hillsides in a waterfall of death from concealed positions with clear lines of fire. Mortar shells rain down on them, the explosions hellacious thunderclaps that rattle their skulls, shake the ground. German snipers take down those cowering on the backsides of trees.

All day the ground shudders, trees explode, sending out rocks, bark, hot metal shrapnel; all day men die.

But like yesterday, the 442nd push forward. Toward the Lost Battalion. Retreat not an option.

* * *

Night descends in the dense forest, cold, inky, heavy, black. Alex is alive. He did not expect to be. Others have died, their dying screams still echoing in his ears. But here he is, heart still beating, digging out a slit trench as best he can with his helmet. Mutt and Teddy beside him, Teddy digging with a trenching knife, Mutt with an empty mess kit.

They dig until exhaustion claims their wrecked arms. Alex, the skinniest of them, squeezes in and scrapes out space at the bottom for their legs, giving the trench an L shape. Without that, they’d be sitting cramped all night with kneecaps pressed up against their chins. They sit on their helmets, the bottom of the trench already filled with freezing water.

They break out their K rations. They eat the cold beans and stale bread grimly, dutifully. A long, savage day; they covered only one mile. Tomorrow, they’ll have to cover two miles to reach the Lost Battalion. They try not to think about this.

The shelling begins an hour later. The ground rocked, tree trunks exploding and spraying out blades of white-hot metal and wood shrapnel. A soldier, on his way to a pond to refill empty canteens, leaps into their trench for shelter. The canteens rattling behind him like shaken bones.

At least the darkness conceals them. The Krauts are only guessing. The hours pass slowly with nothing to do but sit in their slit trenches, eyes heavy, backs screaming, while explosions rip the forest apart, hoping that the shells don’t come any nearer, that the tree bursts stay on the other side of camp, or better yet, move farther afield.

* * *

Alex opens his eyes, not sure if he’s actually slept. His left foot is a cauldron of heat. The pain like scalding hot water being poured on his foot.

“Braddah,” Mutt says sleepily in the dark, eyes half opened. “You okay?”

Alex is not. He has trench foot, a condition caused by the constant exposure to cold and moisture. He knows without even having to look that the skin on his foot is wrinkled and gooey-soft, the tissue beneath infected.

“I’m fine,” he says, wincing.

“Want me to take a look?”

“Nah. Probably can’t even yank it out of my boot, it’s that swollen. Besides, don’t wanna be caught barefoot if they surprise-attack.”

Mutt lights a Camel and takes a long drag. He holds it out to Alex. “I got lots more, brah.”

Alex takes it, nodding his thanks.

Mutt rubs the ball of his hand into his eye. “So damn tired but can’t sleep. Keep hearing them sounds, you know? The screams.” He takes out another cigarette, lights it up, careful to keep the flame below the rim, out of sight from German scopes. Around his ankles, floating in the puddle of rainwater, five or six butts float like sickly water lilies.

A faint drizzle, fine as mist, sprinkles down.

At the end of the trench, someone shifts. The soldier with all the empty canteens. He’s from the 100th Battalion, he’d told them. Fighting since Salerno, over a year ago. He grunts; a moment later comes the hollow sound of water trickling into metal. He’s pissing into his helmet. Finished, he tosses it out, then scoops muddy water from the trench bottom into the helmet. Swishes an expert swirl before flinging that out. Slaps the helmet back on, and is asleep almost immediately, lines of dirty water trailing down his face and neck.

“That’ll be us someday,” Mutt whispers, staring at the soldier. “Seen everything, feel nothing no more. Nothing on your conscience. Can see death all day and then sleep like a baby all night.”

Alex closes his eyelids. Sticks his tongue out to catch raindrops.

“I’m glad Belinda dumped me,” Mutt says unexpectedly, his voice low and soft.

Alex opens his eyes. “What?”

“Belinda. I’m glad she said no.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I proposed. She said no. Got her Dear John letter a few days ago.”

“No way.”

Mutt pulls his rifle against his chest. A condom is wrapped around the muzzle end with a rubber band to keep dry the ammunition inside. “I’m glad. No, really. Because when I get back to Hawaii I’ll be, you know, this different guy. A brute. An animal. Like that lolo chump”—he points to the snoring soldier at the end of their trench—“and nothing like the decent young man she remembers me as.”

Alex shifts his position in the tight quarters. “You’re still the same, Mutt. I mean, you stink right now. And you look horrendous. But you’re the same guy.”

Mutt takes a long drag on his cigarette, flicks the short butt to the bottom of the trench. “We’ve all changed, brah.” He pulls out another smoke. “How’re things with your girl?”

“What girl?”

A small taut smile crosses Mutt’s lips. “Right.” He lights his cigarette, looks at Alex. “The girl you talked about once. In that bar in Hattiesburg.”

Alex shrugs.

“Come on, brah,” Mutt says. “I see you take out that ragged piece of paper every day. The drawing of that girl. I see the way you look at it.”

Alex leans his head back. “Her name’s Charlie.”

“Charlie?”

“Yeah. She’s French. From Paris.”

A moment passes.

“Why you never talk about her?”

Alex stays quiet. Rain falls harder now, filling the air with a static hiss. After a minute, he speaks quietly, his voice barely audible. “We wrote to each other all the time. For years. Shared everything about our lives. But it’s been two years since I last heard from her.” He shuts his eyes. His eyelids feel impossibly heavy, and he can feel a wetness gathering behind them. A minute passes, and another, and he finds himself speaking again.

“On my worst days, I think she’s gone. As in, dead.” He shakes his head. “Or maybe she’s still alive. I don’t know.” He touches the breast pocket of his shirt, feels the slight bulge of folded paper in a waterproof pouch. “Maybe that’s why I keep looking at this drawing. It’s my way of keeping her alive. That make sense? It’s like, the day I don’t look at her is the day

she finally…”

In the distance, a mortar strikes. But it is far away, the sound muted.

Alex takes off his helmet, tilts his head up at the pouring rain. “She seems so far away. Not just her. But my whole life back on Bainbridge Island. The strawberry farm. My school. My dog. Everything that once made me happy. They feel a million miles away and a billion years ago. Like none of it was real.” Raindrops pellet his face, cold and hard, mixing with his tears and making rivulets that flow down his cheeks, his neck. “Even my parents. And my brother, he’s never written back to me, not a single letter. Honest, some days it feels like … none of them ever existed.” He looks at Mutt. “I’m a terrible person, aren’t I, Mutt?”

Mutt gazes at him with red-rimmed eyes. “Nah,” he says softly. “You’re not, brah. You’re not.”

Sometime after midnight the artillery shells start up in earnest again. A macabre display of rumbling lights that strobe over the cratered, befouled forest. Rain falls heavy in this eternal night.

54

OCTOBER 29, 1944

FORÊT DOMANIALE DE CHAMP, FRANCE

The gray dawn vomits its light over the ravaged forest. Those who are alive stumble out of the trenches. Their drenched clothes and skin are the color of sewage, and where soldier ends and forest begins, there is no telling; sometime during the night they have become congealed into a wet sop.

Some cannot even walk. They crawl out, hoping to stamp some life into their trench feet. Others don’t bother. They begin the long crawl back, two miles over mud and tree roots and fallen trunks through ribbons of fog and down the mountain to the aid station.

Alex stares at his left boot for a long time. Gritting his teeth, he wrenches the boot off. His foot balloons out, a bloated mess. He tenderly peels off the wet sock. The skin is a dark blue, almost black, with a waterline on his shin matching the level of water in his boot. Dotted around his ankle, like eyes, are red blotches of open weeping.

“Damn,” Mutt whispers, looking down. He sticks his hand under his uniform, removes a balled-up pair of socks from his armpit. “Here. Dry and warm, right out of the oven.”

“The fresh scent of BO come free?” Alex says, putting it on gratefully. He balls up his wet socks, stuffs them into the pit of his underarm. His swollen foot is near impossible to cram back into his boot. “There,” he says finally, his eyes damp with pain. “Out of sight, out of mind.”

Minutes later, K Company pushes forward. Reluctantly. What they want is to retreat. Or at least hunker down for the day, wait for reinforcements and supplies to arrive. But they have been ordered to advance. By General John E. Dahlquist himself. Because if they don’t reach the Lost Battalion today, those boys from Texas will perish.

And so K Company pushes forward. Through the grater of German minefields, artillery and mortar strikes, tanks, machine-gun emplacements, six hundred enemy soldiers. They push forward even though they’re armed with only nine-and-a-half-pound rifles, bayonets. Push forward even though as a unit they’ve already suffered massive casualties, been cut down to half their size, even though they are at the end of their physical strength. Yet still they push forward with rifle to shoulder, head tilted to aimer, with fingers pressed against triggers, even though they sense—correctly—that they are cannon fodder. That many will perish today.

* * *

By afternoon, there’s good news and bad news.

The good: they’re only one mile from the Lost Battalion.

The bad: they can’t advance. Before them is a narrow uphill ridge with drop-offs so steep on either side, it might as well be a suspension bridge. The Lost Battalion is on the other side of that razorback ridge.

And the worst news: General Dahlquist has ordered K Company to advance. Across the ridge.

“No way,” Alex shouts back to their squad leader, Sergeant Snap Nakai. They’re flat on their bellies, spread on the cold muddy earth. “That’s a funnel of death. It’s booby-trapped with mines, full of concealed machine-gun nests and snipers behind every tree. We won’t survive a direct frontal assault.”

“We’ve got orders!” Snap yells back. “There’s only one way to reach the Lost Battalion. Through that ridge!”

Mutt grabs Snap by the shoulder. “There’s no way—”

As if overhearing and now mocking them, a spray of German machine-gun fire rips into the ground before them. They press against the bark of the large tree.

Zack tightens his helmet straps. “It’s sure death—”

“It’s a direct order from General Dahlquist! We push through at all costs.”

“Screw Dahlquist!”

Snap Nakai glances at the men of K Company to the right and left of him, sheltering behind trees. “This whole battle comes down to us, men. The dozen of us. Right here. Because we’re the tip of the spear. We decide if the Lost Battalion gets saved or not. Just us.”

A mortar shell strikes nearby. The men duck, their ears ringing.

“We’re not cowards, sir,” Teddy shouts over the bedlam. “But we’re not stupid, either. That ridge is suicide.”

“Listen to me!” Snap Nakai shouts. “Everyone who’s died fighting, died to get us to this point.” He grips and regrips his machine gun. Looks to his men. “Now shut up and be soldiers. On my go.” He stares ahead, swallows hard. “Now!”

They rise as one, sprinting out from the protection of the trees.

They get about ten yards. A barrage of machine-gun fire mows them down. They fall, all of them, most ducking behind trees for shelter, a few facedown in the mud, dead. Zack’s fallen, but he’s not dead. He’s on his back, twenty yards away, clutching the side of his stomach. Blood pouring out of an open wound, blackening the mud. Writhing in pain out there in the open, trying, vainly, to lie still. To not catch the attention of snipers.

Mutt leaps out from behind the tree.

“No, Mutt!” Alex grabs his shoulder. But he’s too late.

Before Mutt can even get into the open, German guns open up on him. He retreats behind the tree, cursing.

A sniper shoots, striking Zack’s thigh. He curls in agony, drawing up his leg. A moment later, another shot. This time the other leg. In the ankle, shattering it. The boot—always too large for Zack—goes flying off. Zack howls even louder, a lonely, pain-filled sound. They’re toying with him, a cat with a maimed mouse.

“Gotta get him, gotta get him,” Mutt says, his face flushed with anger, his body tense and ready to spring. But even he knows there’s nothing that can be done.

Another sniper shot. Into Zack’s shoulder.

Silence. They think Zack is dead now, mercifully. But then he starts wailing, a terrible pain-drenched howl, “Okaasan. Okaasan.” He’s crying for his mother.

Then a single crack of the sniper.

Zack’s head explodes.

And with that, the mortar shells once again fall from the skies, and the fusillade of bullets rip the ground and trees apart. There’s no choice now. Under such a barrage, they need to retreat.

Except.

A soldier in the next tree over. Teddy. Lazy Teddy. Incompetent Teddy. Homesick Teddy who was always last in the drills, last in the forced marches, who always just wanted to be with his family, even if it was back in a tar-papered barrack in an internment camp. He’s unsheathing his M1 bayonet, attaching it to his rifle. An obsessed, almost manic fire burning through the prism of tears in his eyes. He doesn’t say anything, doesn’t even look at the other soldiers. But something is coming over the others as they watch him; and in the next moment they, too, are unsheathing their M1 bayonets, attaching them to their rifles.

Teddy rises and, with a scream, charges. He is yelling, in Japanese, in English, it doesn’t matter, not now. With tears in his eyes, with blood pouring down his face, with lice in his hair, venereal disease in his groin, fatigue in his bones, grief and anger in his heart, this boy who always sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” the loudest, who loved nothing more than fishing rainbow trout in the Fryingpan River of

Colorado with his pals on a hot summer day, who dreamed of one day marrying the pretty Jenny Anderson, now charges up the ridge, shooting a Tommy from the hip, spraying bullets.

“GO FOR BROKE!” he yells. “GO FOR BROKE!”

And with that cry, the others rise as one behind him, and charge up the ridge as the earth explodes around them. Alex’s painful trench foot forgotten in this hot mix of adrenaline and fear and violence.

Teddy goes down in a hail of bullets. But he rises in the next moment like a miracle, his legs wobblier, his eyes more fanatical even as life gushes out of him. He throws a grenade, and this boy who couldn’t hit the ocean from a yard above it somehow lands it right in the machine-gun nest. It explodes, sending up German soldiers and metal fragments. And still he charges up, his company right behind him, still he is yelling and screaming, his expended Tommy tossed away, firing his bayoneted rifle.

“Banzai!” he shouts. “Banz—”

The bullet catches him in the neck. This time, he stays down. Blood spurting out from his neck, the artery severed. By the time Alex and Mutt reach him, he’s dead. Alex grabs Teddy’s rifle, charges up the hill, only he is faster now, and more accurate. Anger sharpens focus.

Next to him, Mutt. Armed now with a BAR weapon that he picked up from one of the dead. Aiming at a machine-gun nest, he unleashes a torrent of gunfire. As he does, Alex runs around the side of the nest, certain that at any moment he’s going to be seen and shot.

But he isn’t. He leaps over the lip of the nest, spraying his machine gun into the backs of the four Germans until the clip is expended.

“Maki!” Mutt shouts, reaching the nest. “Okay?”

“Okay,” Alex shouts back, throwing away the machine gun and grabbing a German one. “Cover my back!”

Mutt finishes reloading his BAR. “You cover my back.” And he is leaping over the edge of the nest, charging uphill for the next.

The Hunt

The Hunt The Trap

The Trap The Prey

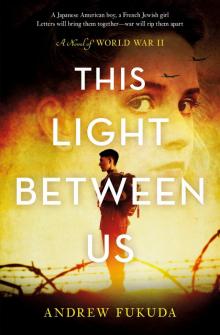

The Prey This Light Between Us

This Light Between Us