- Home

- Andrew Fukuda

This Light Between Us Page 2

This Light Between Us Read online

Page 2

A few more families arrive. Including the Tanner family. They slide into the pew in front of Alex.

His back straightens. The Tanner family is well-to-do and highly respected. Their daughter, Jessica Tanner, is popular at school, and now sits down directly in front of Alex. Although they’ve known each other for years, and share the same homeroom at school, they’ve rarely spoken.

The congregation is called to worship, and rise. As they begin to sing, the scent of mint and a vanilla extract floats into Alex’s nostrils. From Jessica Tanner. He’s sure his own breath is foul and egg-soured and wafting down her back. He lifts the hymnal to block his breath.

Next to him, his parents are singing with religious fervor and abandon. The Japanese hymns have been replaced, and the archaic King James English with its thees and thous is throwing them off, making their thick accents even more garish. That doesn’t stop Father, though. An elder and leader of the Japanese congregation, he’s known for his demonstrative singing. But this morning Alex wishes Father would stop singing because the Tanners—especially Jessica Tanner—can hear each and every butchered syllable.

After the song ends, Pastor Ken smiles at the congregation and exhorts them to greet one another.

“Henry,” Mr. Tanner says, turning around to Alex’s father. Nobody ever calls Father “Henry” except white people who stumble over “Fusanosuke.” He extends his hand out to Father. “How are you this morning?”

“Good. Real good.” Father takes his hand with a wide smile, baring his crooked yellow teeth. His sun-darkened farmer’s skin is an embarrassing contrast to the white complexion of the Tanners.

Next to him, Alex’s older brother, Frank, is play-punching Josh Tanner. They’re teammates on the Bainbridge High football team, Josh a wide receiver, Frank the star quarterback, and they’re talking about that afternoon’s practice, and how they’re going to destroy Vashon High School on Friday—

Jessica Tanner turns side to side, looking for someone to greet. She starts whirling around. Toward Alex.

He panics. Looks down—

“Hi, Alex,” Jessica Tanner says brightly. She holds out her hand.

Hesitantly, he takes it. Her skin is so soft and porcelain smooth. His own calloused hand, which only an hour ago was cleaning out the chicken coop, is a monster wrapping itself around a swan.

“Looking forward to the game on Friday?” She’s looking at him with a friendly, focused gaze.

“Y-yeah.” His throat is thick and clogged. She seems even more beautiful up close. Her eyes are a blue that even the purest sky would envy. There’s a faint splatter of cute freckles over the bridge of her nose he’s never noticed before. “You?”

“We’re gonna crush ’em,” she says, winking before turning around.

Everyone sits. He’s still holding the hymnal in his left hand, and as he reaches forward to place it into the holder, Jessica Tanner flips back the long sweep of her hair so it doesn’t get caught behind her. Her hair waterfalls over the back of the pew, and pools softly on the back of his hand still on the hymnal. A few strands of her hair slip through the small spaces between his fingers.

He freezes. Can’t breathe. Jessica Tanner’s hair is on his hand, between his fingers. Strands of gold, the softness of lips.

And then it happens. The doors of the church slam open.

Everyone jolts and spins around. Jessica Tanner’s hair flies off Alex’s hand.

Backlit by the outside light and framed by the doorway, Bruce Fukuhara—a senior in high school who defiantly stopped coming to church a year ago—pauses. He looks around, panting, sweat beading his acne-ravaged forehead, unsure of what to do. Then he rushes up the center aisle to Pastor Ken in the pulpit.

Everyone leans forward. They’re all curious; they’re all guessing.

Somebody has passed away.

Somebody’s fishing boat has been vandalized, or worse, pillaged.

The price of strawberries or celery collapsed overnight.

But it’s none of these. It’s far worse.

Pastor Ken frowns as he listens to Bruce. His face goes white; his left hand trembles as he leans on the pulpit.

“I’m sorry,” Pastor Ken says, and Alex will always remember those first words of apology, how they might have set the tone for what is to come. That maybe if Pastor Ken hadn’t apologized as if he were somehow responsible, as if they were all responsible, perhaps things would have turned out differently?

“But I have just learned…” He swallows, stares down at his Bible. “This morning, a few hours ago, Japan attacked Hawaii.” His voice cracks. “We are at war.”

Someone gasps. Most sit in shock, hands covering mouths. Mrs. Tanner clutches her son’s arm, her fingertips going white. Josh Tanner is old enough—or will be, in a few short months—to enlist.

Pastor Ken murmurs something about the need to pray in this time of—

A white man stands. This single action so decisive, it shuts up Pastor Ken as effectively as if he were slapped. The man looks around, almost frantically. He finds what he’s looking for two pews away. Another white man. He stands, too. And soon it seems all the white men and white women and white children are gathering together, their voices getting louder. With stern expressions as they look around. This is what they must see:

Not Henry and Joe and Bruce and Tim and Cindy and Janet and Susan. But now Fusanosuke and Hideo and Kaito and Hidejiro and Hitomi and Kayo and Megumi. The exotic, the yellow, the inscrutable. The enemy.

One thing is clear: church service is over.

“Come on,” Father whispers to Alex, leading his family out of the pew. The other Japanese families follow suit, quietly leaving the sanctuary. The church isn’t theirs; it never was.

Alex and Frank hop into the cargo bed of the pickup while Mother sits in the front cab. Father speaks curbside to a group of Japanese men: each is to drive his own family back home, then head over to Father’s place. He’s the only one with a radio.

One by one the cars leave the church parking lot. Orderly as a funeral procession.

The town center is strangely quiet. The few people strolling about seem oblivious to what is happening, to how history has just veered off course.

Father drives just below the speed limit. At the last intersection before leaving the town center, the traffic light turns red. Father stops. Across the street, outside a tavern, a group of men in denim overalls are huddled around a transistor radio.

One of them peers up at the line of pickup trucks, then back down to the radio. A second later, his head snaps up like a man who can’t quite believe his eyes. His gaze sweeps across the three vehicles behind, at the drivers and passengers. He mutters something, and the other four men stand up.

They come as one, their anger raw. Elbows crooked, eyes red-rimmed, cheeks scruffy. Frank leaps forward in the cargo bed, pounds the cab window. “Go, Father, just go!”

Father slams the pedal right as the five men close in. Alex feels something moist strike his cheek. Spit. Then a cussword, swallowed up by the squeal of tires. They take off, all four trucks, in a cloud of swirling dust.

No one speaks as Father speeds home. Alex stares at the passing farmlands, his thoughts like flies buzzing over roadkill, flighty and restless. The football Frank normally cradles is left forgotten on the floor of the cargo bed. It rolls around, side to side, back and forth. Nothing seems anchored anymore, everything is dislodged.

Back at the farm, they hurry into the house. Hero comes bounding toward them, wanting to romp. But he stops, head cocked, sensing something wrong. Whimpers. Mother and Father speak in hushed tones even though there’s no one around for miles.

Alex doesn’t change out of his Sunday clothes. No one does. Father is at the kitchen table, turning on the radio usually used to receive sumo news from Japan. Mother starts boiling water. Frank leans against the counter, his fingers tapping, tapping. Static hisses from the radio. Father works the dial. A voice blares out, angry and declarative.

The report dies out to a wave of static. Father turns the dial, finds another live report from Honolulu, Hawaii.

“… we have witnessed this morning a distant feud from Pearl Harbor, a severe bombing of great intensity with considerable damage done. This battle has been going on for nearly three hours—” The report suddenly cuts off.

The water boils. Mother brings tea to the table. But neither she nor Father drinks. They sit rock-still, their faces stoic and unreadable, heads bowed toward the radio as if in apology. Father turns the dial, finds another report that Japan has begun to attack Manila. A minute later and the radio channels have resumed their regular programming.

Alex leaves the kitchen. He shuts the door to the bedroom he shares with Frank, sits at his desk. He thinks about the regular programming that has resumed on the radio. As if the attack on Pearl Harbor isn’t actually such a big deal. A minor skirmish, a boys-will-be-boys scrape. Dust off, shake hands, move on. Perhaps life will go on as usual? He stares outside. The day is bright, the sky blue, the sun blazing and glorious. As before. As usual.

But then he thinks about the group of men back in town. The way they approached the truck, elbows crooked, hands bunched into fists. The hatred in their eyes.

Nothing is the same, he thinks. Everything has changed.

From outside his window, a sound: whack. Coming from the barn. Whack.

Alex knows the sound. Years ago, Father hung an old tire on the cypress tree by the barn. The two brothers spent endless hours swinging on the tire until they outgrew it. A year ago Frank turned the tire into a football target, throwing the pigskin through it from varying distances, often on the run, sprinting right, breaking left, the tire swaying like a pendulum, the football sometimes striking rubber, usually sailing right through.

Alex goes to the window. He sees Frank at the tire. Hero standing at a distance, ears pinched back. Frank is holding a baseball bat. He raises it above his head, then swings it down on the tire furiously like he’s splitting firewood. Whack. Whack. Even from the window, he can see his brother’s chest heaving, his Sunday clothes twisted and disheveled. The bat rises again. Falls. Whack. Whack. Whack.

3

DECEMBER 8, 1941

On Monday morning, less than twenty-four hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, Alex steps off the school bus. He has never in all his life ever felt his Japaneseness more keenly.

He tugs down his woolen hat, wishes he had a pair of sunglasses. As he walks to the front entrance, every eyeball at Bainbridge High School seems to turn to him. Or maybe not, maybe no one is paying him any mind. Maybe he’s as invisible as always. The Nisei students tend as a rule to be unseen in this community, anyway, but even among them Alex usually goes about unnoticed.

Not that he especially minds. So long as he has his ABCs—Art, Books, Charlie—he’s fine.

Mr. Johnson, the gym teacher, stands on a landing at the top of the stairs before the entrance. This is unusual; Alex has never seen Mr. Johnson out here. He’s greeting the arriving students with an enthusiastic “Good morning, God bless America,” thumping the shoulders of some of the bigger boys. An American flag is pinned on his jacket. When Alex walks past, Mr. Johnson clams up.

In the hallway, Alex keeps his eyes on the floor. He stops by his locker to throw in his jacket, then slams the door shut. His homeroom is only three steps away, and he takes a deep breath before entering the classroom.

Surprisingly, it’s business as usual. Craig Webster and Jack Wells are goofing around. Josh Hunter is carving into the wooden desktop with a penknife. Leo Dalton and Jimmy Myers are arm wrestling, grunting red-faced. Mary Billings is copying homework. Charlotte Coplin is brushing her hair, pretending to ignore the gawking boys.

Only Billy Hosokawa, probably the funniest kid in class with his Daffy Duck impersonations, seems out of sorts. He’s sitting alone, hunched over and perfectly still. Like a tiny mouse caught out in the open field as eagles circle overhead.

Mr. Hartford tromps in. The class rises as one, chairs scraping against the wood floor. Mr. Hartford’s face often has a reddish hue to it, and there are rumors of a drinking problem. But this morning there’s a harder tinge to the redness. The red of anger.

“Good morning, everyone.” His eyes shine with an uncharacteristic clarity.

“Good morning, Mr. Hartford,” everyone chimes back in unison.

He pauses a moment, taking in the class. When he sees Billy Hosokawa, his salt-and-pepper moustache twitches with annoyance. He unfolds a sheet of paper.

“I have an announcement to make. From Principal Roy Dennis.” A look of mild disgust crosses his face as he reads aloud.

“‘Yesterday, Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. We are right to be angry about this. But we must not let our patriotic anger boil over into an unrighteous rage. I want to remind everyone that the Japanese American students here at Bainbridge High School are not only our fellow students but our fellow Americans. We will have no part of race hatred at our school today or any day. God bless America.’”

Mr. Hartford stares at the paper. In a blur of movement, he suddenly scrunches it up into a ball. The sound is impossibly loud, almost violent. He tosses it into the wastepaper basket across the room. Then squares his broad shoulders to the classroom, and stares at the American flag on the wall.

“Let me,” he says, “translate what Principal Dennis just said. Yesterday the Japs attacked us. A sneak attack I can only describe as cowardly and gutless.” His face twists into a scowl. “But they picked the wrong country, didn’t they? Because when we get punched, we punch back, don’t we, fellas? And no country punches back harder than the United States of God Bless America. So you just watch, we’re going to punch every rat-faced, squinty-eyed, bandy-legged Jap, every last one of them I’m telling you, all the way back to Tokyo.”

Some of the boys clap and booyah! Alex stays very quiet. Anthony Donner raises his hand and asks Mr. Hartford how long it’ll take President Roosevelt to officially declare war on Japan. “Before this day is done, and I’ll bet my britches on it,” Mr. Hartford answers, jutting out his meaty chin. “On that note, it’s time for the Pledge of Allegiance.”

The class recites the pledge louder that morning than any other time. Mr. Hartford, hand over heart, gets misty-eyed. Alex makes sure that his voice is neither too quiet nor too loud. And when the class sits down, he is similarly careful that he isn’t the first or the last to sit, that he stays right in the middle of the pack.

When he walks out into the hallway ten minutes later, it’s as if he’s grown a second head and become covered in leprosy. Every eyeball turns toward him. Whispers, whispers. And stares, glares. He keeps his eyes down. He has never felt so conspicuous.

A tall senior bumps into him, almost knocking his books to the floor. An accident, probably. But by the end of the day, he’s bumped two more times. When he goes to his locker to retrieve his jacket, he notices something scrawled on the front. Three words.

Go home Jap.

The three words are short, blunt, and cut deep. Alex has only wanted to be left alone. But now someone has thought of him. Someone has taken the effort to write these words on his locker.

He reaches forward to wipe the words away. But the ink holds, smudging only a little.

A group of girls, walking past behind him, start to giggle. Probably at something unrelated, probably they haven’t even noticed the words.

A few lockers down to his left, a boy laughs.

He should walk away. But he is frozen, unable to pick up his feet.

Someone approaches him from behind. Puts a warm hand on his shoulder.

“Alex.” It’s Frank. “I already spoke to the janitor. He’s gonna take care of it.” Frank squeezes his shoulder. “C’mon, let’s go.”

Al

ex nods. He tucks his head down and together they head down the hallway. Frank walks right next to him, and Alex is glad for it. He wonders if Frank has any idea how much he worships the ground he walks on, how his heart swells with pride every time he walks past the trophy case at school and sees Frank’s beaming face on the team photograph, front and center. How, at home, Alex secretly watches him practice for hours on end, throwing the pigskin through the swinging tire or into open trash cans placed at specific distance markers. Because it’s super popular Frank, with his ungodly athletic prowess and aw-shucks grin and happy-go-lucky personality, who is the sole reason why skinny, introverted, and more-than-slightly strange Alex Maki hasn’t been bullied mercilessly at school. Nobody touches the star quarterback’s little brother.

When they get on the bus, Frank, for the first time in years, sits next to him. Without speaking a word, they ride home together.

4

* * *

December 10, 1941

Dear Charlie,

Can’t believe it’s been only three days since the Pearl Harbor attack. This has been the longest week of my life.

There’re all these dumb rules for the Japanese American community. No traveling more than five miles from home. No radios. Our bank accounts frozen. Yesterday we had to register ourselves at the police station and turn over contraband. I even had to give up my pocketknife and flashlight. Just in case, I—yes, me, scrawny Alex Maki, the skinniest bookworm from sea to shining sea—decide to lead a revolt at night armed with nothing more than my puny pocketknife.

At school no one speaks to me. There are a few other Japanese American students but we avoid each other. I guess we don’t want to come across looking like the enemy, plotting an attack on America or something ridiculous like that.

The Hunt

The Hunt The Trap

The Trap The Prey

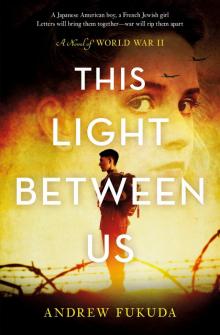

The Prey This Light Between Us

This Light Between Us