- Home

- Andrew Fukuda

This Light Between Us Page 3

This Light Between Us Read online

Page 3

My homeroom teacher, Mr. Hartford, has been sober for the whole week. Yes, Mr. Drunk himself. On Tuesday he flat out told Billy Hosokawa and me that he didn’t want us reciting the Pledge of Allegiance anymore. He told us we should stand out of respect, but he didn’t want “no Jap” defiling the flag. If I was blond with blue eyes and had a surname like McCarthy, I’d have told him to go to hell, no one is stopping me from pledging my allegiance to my home country. But all I did was stare down and wish I could disappear through the floorboards.

But I get the last laugh. Because I’m still saying the pledge every morning. I whisper it secretly like a ventriloquist. Mr. Drunk doesn’t have a clue. Betty Baldwin sits in front of me, and she hears. She always gives me a quick sideways wink as she sits down.

I’m sorry that this letter is all doom and gloom. They say writing helps clarify your thoughts and emotions. Well, it has. And my thoughts and emotions are clearly just the darkest of clouds pouring down the bitterest of rain.

Alex

* * *

Alex leans back in his chair, rubbing his hand. Night presses against the window. In the darkened glass, he sees the reflection of the small guttering candle on his desk. He sees his own reflection, too, his thin arms poking out of the blanket thrown over his hunched shoulders.

He folds the letter and inserts it into a stamped envelope. Later today, he’ll drop it into the mailbox where it’ll begin a five-thousand-mile journey to Paris: first from Bainbridge Island to Seattle to New York City, then a long flight to Lisbon, Portugal. Then by rail across Spain and into the zone non-occupeé to a town called Perpignan where it’ll hopefully slip past the prying eyes of censors, and arrive at long last in Marseille.

There a man named Monsieur Wolfgang Schäfer, to whom the letter is addressed on the envelope, will pick it up. Monsieur Schäfer, a close friend and business partner of Charlie’s father, is an exceedingly well-connected and influential industrialist in possession of great wealth and, importantly, the necessary travel documents. He makes biweekly business trips to and from Paris, and his briefcase, which is always stuffed with documents and contracts—and on occasion a letter from or addressed to Bainbridge Island, USA—is never searched.

“Alex,” a voice says from across the room.

Alex almost cries out. “Frank? You scared the hell out of me.”

Frank laughs quietly. “What time is it?”

“Almost three.”

“Dang. The dead zone.” He rubs his eyes with the balls of his hands. Ever since Pearl Harbor, he’s been waking up at all hours, very unusual for him especially during football season.

“Can I ask you something, Frankie?” Alex hasn’t called his brother “Frankie” in years.

But Frank doesn’t seem to notice, much less mind. “Go ahead.”

“What’s going to happen to us?”

Frank stops rubbing his eyes. “What do you mean?”

“I mean, are we okay?”

Frank stifles a yawn. “I’m too sleepy to read your mind. Just spit it out. What’s buggin’ you?”

Alex lifts the pen nib off the page so it doesn’t blot. “Are we going to be, I don’t know, expelled from school or something?”

“Expelled from school?” He snorts. “Whatever the hell for? Don’t be ridiculous. Nothing’s going to change, okay? We’re Americans, born and raised.”

“How about Mother and Father? Will they be sent back to Japan?”

“Nah, don’t be stupid.” Frank pulls himself into a sitting position, his knee bent, an elbow resting on top. His eyes tired but wide, the flames of the candle flickering softly over his face. A handsome face, breaking into full manhood, gazing at Alex. “Everything’s going to be fine, kid.”

“Will they let you stay on the team? And still be quarterback?”

Frank gives a cocksure grin. “Now I know you’re nuts.” He rubs his thick forearm. “Without me, there is no team. And just today, Coach was telling us we’re going to be busier than ever. Maybe play some charity games after the season, raise money for the military.” He leans toward Alex. “Nothing’s going to change, Alex. Everything will be fine, you worrywart.”

Alex stares out the window, then back at Frank. “I hope you’re right. Because I heard rumors about roundups and other stuff.”

“Hey, when have I ever been wrong? Don’t worry.” He flicks his chin at Alex’s desk. “Whatcha drawing?”

“Not drawing.” Alex pauses. “Writing a letter.”

“To Charlie again?”

“Yeah.” Alex turns his eyes away, a little embarrassed.

“It’s good to have a friend,” Frank says softly after a moment. “Especially now.”

“Really?”

“Yeah.”

Alex hesitates, puts the pen down. “Frankie, can I ask you a question?”

“Shoot.”

He pauses. Then whispers, “Do you think I’m weird?”

“Of course you are, you little goober.” He leans forward, rests his chin on his kneecap. “But what do you mean?”

“Never mind.”

“No, seriously, Alex.” His face curious but also tender and protective.

Alex stares down at the page, swallows. “Is it normal to … feel this way for someone I’ve never met?”

“And what is this way?”

Alex shrugs. “I don’t know. Just like, real close. Like we’re best friends. But maybe even closer than that.”

“Closer than best friends? Yeah, that’s called a girlfriend.” He clucks his teeth in amusement.

Alex shakes his head. “Never mind.”

Frank’s voice turns earnest. “Hey, I’m just joshin’. Look, I think it’s fine, kiddo. Not everything has to have a clear label. You can be somewhere between best friend and girlfriend, and that’s a perfectly okay place to be.” He rubs his bicep. “She feel the same way?”

“I don’t know.”

“You’ve never told her how you feel?”

Alex pauses before answering. Soon after he turned fourteen, he’d confessed his feelings to her in a feverish, blathering nine-page letter. Two seconds after he dropped the envelope into the mailbox he wanted to reach into the slot and retrieve it. But it was too late.

She didn’t reply for six weeks. The longest period he’d gone without hearing from her. He thought maybe this was her way of ending things, ending the awkwardness. He wished he’d never sent that letter.

He returned home one day to find a letter from her. He ripped open the envelope. In reply, she told him he was—

“Well?” Frank says. “You ever tell her how you feel?”

“Once I might’ve confessed my feelings.”

“Yeah? How’d she respond?”

Alex pauses. “She basically called me an idiot.”

Frank laughs, not unkindly. “Too funny. And true.” He grabs his pillow, throws it at Alex, hitting him on the head. A perfect strike. Of course. “Because you are an idiot, kid.”

Alex picks up the pillow and throws it right back. It thuds against the side of the bed, missing badly, and flops to the floor. Of course.

“You guys ever talk about it again?” Frank asks.

“Nah. We just let it drop.”

“And how were things after? Weird?”

Alex stares down at his hands. “We … actually got closer. I don’t know, maybe it showed we could be completely honest with each other?” He shrugs. “Something like that.”

Alex is half expecting Frank to rib him again. But when he looks up, Frank is gazing at him with a strange expression. “In some ways I really envy you,” Frank says.

“You envy … me?”

“Yeah. To have a friend that close.”

“You’ve got friends all around! You’re Mr. Popular!”

He looks down to the floor. “Yeah. But no one really that…” He shakes his head. “Nah, never mind.” He picks up his pillow, plumps it into shape. “But do me a favor, okay, Alex? Maybe you should, like, go o

ut on a date once in a while. Take a gal out to the Bowlmoor. Or the drive-in some Saturday night. Take someone. Just so, you know…”

“Just so what?”

“Nothing.” He lies down, settling under the blanket. He looks at Alex, head on pillow. “Just so you stay grounded. So you stay real. So you don’t get too lost in fantasyland.” He turns to the wall, and a minute later is asleep.

Alex stays at his desk a while longer. Not to finish writing his letter. Instead, after Frank starts snoring, he opens up the drawer and slips out a letter he’s reread countless times. He unfolds its page with all the care of a museum archivist over an artifact. The pages were once lightly perfumed, and Alex likes to imagine he can even now detect a lingering whiff. He turns to the paragraph where Charlie had called him an idiot. He’s read this paragraph countless times; not because he particularly enjoys being called an idiot, but because of what follows.

… you’re an idiot, Alex. Because you don’t say these kinds of affections now. Not at 14 years old, not when we don’t have a chance of seeing each other for many years. No: you say it when you are 18 or 19, when you are old enough to travel to Paris and see me. When you are old enough to—maybe as a university student!—live here. That is when you say, “I love you.” You are an idiot!

She never brought the topic up again, thankfully. But even now her words—every curlicue and loop of each character indelibly etched into his mind—bring a small smile to his face, and make his heart, even after almost three years, beat a little faster.

5

DECEMBER 11, 1941

Alex wakes before the crack of dawn. Picks his head off folded arms, his neck creaking. A pool of drool splotches his letter, next to a blot of ink where his pen bled. It’s his morning to do chores, and with a groan he pushes off the desk.

He walks down to the kitchen, fills a glass with water. A voice suddenly whispers in Japanese, “Your turn for chores?”

“Father?” He almost drops the glass. “I didn’t see you.” He walks over to the kitchen table, pulls out a chair. Sleep lines crease Father’s face. He’s been down here all night. Nobody is sleeping well these days.

An almost-empty bottle of sake sits on the table. Beneath the faint aroma of alcohol, Alex smells damp soil and strawberry wafting from Father’s clothes, from the pores of his leathery, prematurely withered skin. Spread out before him, letters and postcards and aerograms from Japan lie scattered around the bottle. When Father drinks—which isn’t often—he becomes sentimental. He’ll bring out old letters and talk everyone’s ears off. This is how Alex has learned of Father’s past: through the vapor of sake, beer, whisky, the spillage of slurred words.

It’s in those moments, looking into Father’s drunken eyes (the only time he can gaze directly into them), that Alex sees the restlessness rooted deep into the bones of every immigrant. That spirit of adventure that made Father gaze across the seas and wonder about a land called A-me-ri-ka. When the economy in Japan and especially his prefecture collapsed, he left his parents and two older brothers, and set sail. And never once looked back.

When Father speaks of his first years in America he speaks of the adventure lived. He never mentions the hardships endured, or the racism faced. He speaks only nostalgically and even gloriously of his days working at the Port Blakely Mill—a sawmill on Bainbridge Island that had taken to hiring immigrant Japanese after its usual supply of Chinese laborers was cut off by the Chinese Exclusion Act. The work was hard but the pay at least steady. And the community of Issei was tight-knit, living together in a segregated settlement of barracks built along a steep hill. Yama, they called it. “Mountain.”

When the Port Blakely Mill folded, the Issei looked elsewhere for work, and they didn’t have to look far. For years, they’d noted the soil of Bainbridge Island, how it seemed suitable for fruit agriculture. And there was ample land on this sparsely populated island that was occupied only seasonally by wealthy Seattle families in summer homes. The Issei community spread themselves across the island, and with no-nonsense grit, cleared land, removed tree stumps using horses, and blasted the ground with dynamite to clear it of glacially deposited rocks.

In that way they went from millworkers to strawberry farmers; in that way they went from immigrants to settlers and then neighbors. Their roots dug deeper into this American land with each new strawberry harvest, and deeper yet with each new birth of what never stopped being miraculous to them, their American child.

“Before your grandma died,” Father says now, “she would write twice a year. On my birthday and on the date I left Japan.” He runs his fingertips over yellowing envelopes. “I wish she could have met you and Daisuke. She’d have been so proud.”

So unexpected, this tenderness. Father could be like that, spring on you a sudden softness. He was usually an uncomplicated man of authority, and this authority was absolute and total. Over his wife. His boys. Over the chickens whose necks he wrung and slashed, over the land he tilled and browbeat into submission. Even seemingly over the weather itself by sheer force of his indomitable immigrant will.

But one day when Alex was seven, perhaps eight, something happened after which he never saw Father quite the same way. They’d gone downtown, the two of them, to buy supplies. They were in a hardware store, just leaving, when Alex went to the restroom. When he came out, he saw through the storefront windows Father waiting outside on the street, hands clasped behind his back.

Then.

A school bus—yellow, massive—screeched to a halt. Its appearance was like a large background stage prop sliding behind Father. The bus was packed with a visiting junior-high-school baseball team.

Father turned his back to the bus, faced the storefront window. For a second his eyes seemed to meet Alex’s; but then they slid away. The storefront glass was a mirror in the bright sunlight.

The students in the bus were staring outside, bored and hot. Damp hair stuck to their sweaty faces.

The traffic light was still red.

One of the players spotted Father. His lips twisted into a sneer. He mouthed something, thumped the bus window.

Don’t, Father, don’t turn around—

Father turned around. Like a stupid, obedient dog. His neck twisted awkwardly as he gazed upward. He seemed so impossibly small and tiny. So ridiculously out of place.

The teenage boy had a rash of angry zits, and he shouted something. He was excited now. Another boy joined him at the window. They were all angles and bones, these boys. They pointed at Father, the tips of their fingers turning white against the glass.

At the next window, another boy, then another, gawked at Father.

Father gazed back at them, his neck contorted.

Turn around, Father, stop staring back—

The traffic light was still red.

One of the boys pulled the corners of his eyes down into a slant. Puckered his lips, buckteething the upper row. Alex couldn’t hear the boy’s laughter, but the sight of those white teeth and deliriously happy faces seemed to possess its own horrific sound.

Father finally turned around.

They pounded the windows louder, rattling them. A boy pulled down a window. Now the gales of laughter rolled out of the bus like a hot tongue. From even inside the store, Alex could hear the meanness in them.

And all the while, Father did nothing. Stared expressionlessly down the street, his back to the yelling kids, the pulled eyes, the intoned accents.

For the first time in his life, what Alex felt toward Father wasn’t fear. It was shame.

A police officer came walking around the corner, drawn by the hooligan sounds. He was about to yell at the kids when he saw Father. His stance changed. Now he turned to Father. With a flap of his hand, he waved Father along. Like Father was the offending one.

And he did. He moved along. With a nod, a nervous smile.

Everything changed that day. With that courteous nod, that accommodating smile, a bubble burst in Alex’s mind. He never saw Father the

same way again. Father went from being a leader in the Japanese community, a towering being of complete authority—almost a deity—to what he was. An immigrant. A foreigner. A mocked, clueless, misplaced immigrant, put in his place by white boys, kowtowing to all.

When Alex exited the store, the bus was already gone. Father was standing halfway down the other street. Alex went to him, not knowing what to say, if anything at all. Father’s expression was the same as usual. Stoic and unreadable. Without saying a word, they walked to the truck parked a few blocks away. Got in. Drove down the street, out of town.

They didn’t talk on the ride home, not about the bus incident, not about anything at all. It was like it never happened. It was a rock cast into a flat lake; and when the ripples faded it was as if nothing had ever disturbed the water. But the rock was still there, buried deep and hidden, like a lump in the throat.

So strange, Alex had thought, that you could love someone so much, yet also be so ashamed of that same person.

He looks at Father now sitting at the table. At home, away from the outside world where he is regarded a dithering fool, he is the accepted anchor of this family, giving stability and protection. He fills his sake cup one last time, tosses it down, his eyes watery.

“Well, since I’m up anyway,” he says, “might as well get an early start.” He places the envelopes and aerograms and postcards carefully back into the shoebox. “Maybe you should get an early start on your chores, too.”

Alex nods. Outside, a gout of purple-pink is breaking the horizon; in a few minutes, the dawn sun will poke shyly but decisively through.

Father rubs his face with his coarse palms. “I know it’s hard work. I know it’s no fun. So study hard, Koji-kun. Get into a good college, then dental school, right? You’ve got the brains, certainly. Then you won’t ever have to clean out chicken poop. You can leave this farm and live in the big city. A nice house in the suburbs of Seattle. Come by on weekends to visit us.” He nods at Alex. “Right, Koji-kun?”

“Yes, Father.” He lowers his eyes quickly. Truth is, he doesn’t want to be a dentist. But what he really wants to do—what he dreams about, spends endless hours fantasizing about—that’ll break Father’s heart.

The Hunt

The Hunt The Trap

The Trap The Prey

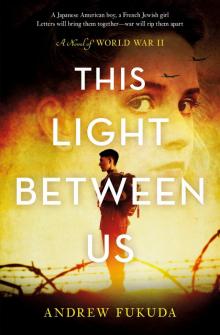

The Prey This Light Between Us

This Light Between Us